On Labels, Authorship, and the Art of Haochen Ren

- Jul 29, 2025

- 5 min read

Written by Sophie Nowakowska In museums, we’re told, quietly but persistently, that whatever is in its space is art. The institution decides, the label confirms, and the audience follows. The label becomes not just an informational tool but a gatekeeper: here is the title, the year, the medium, and the artist's name, all delivered in a sterile format that implies objectivity while subtly instructing us how to look, how to feel, and how to understand. Haochen Ren’s work exposes this sleight of hand by refusing the neutral authority of the label. In his practice, the label is not a passive accessory but the central character, the very medium through which he critiques and reconstructs the institutional logic of contemporary art.

'no title' 2023 - ongoing

In no title (2023–ongoing), Ren presents two labels: one reads, "Please look at the label on the left, 2023," and the other, "Please look at the label on the right, 2023." Together, they form a closed circuit of instruction, a loop with no external referent. There is no object to stabilise the gaze, no artwork to decode, no context beyond the labels themselves. The viewer, caught between two contradictory imperatives, is invited to recognise the absurdity of their own trained behaviour, to follow instructions that lead nowhere. What unfolds is not an encounter with an artwork but an encounter with the conditions of art viewing: obedience, expectation, and the desire for meaning. Ren turns the museum label from an explanatory device into a conceptual trap, revealing how much interpretive authority we unconsciously grant to text over an image and how fragile that authority becomes when it's exposed as a linguistic tautology.

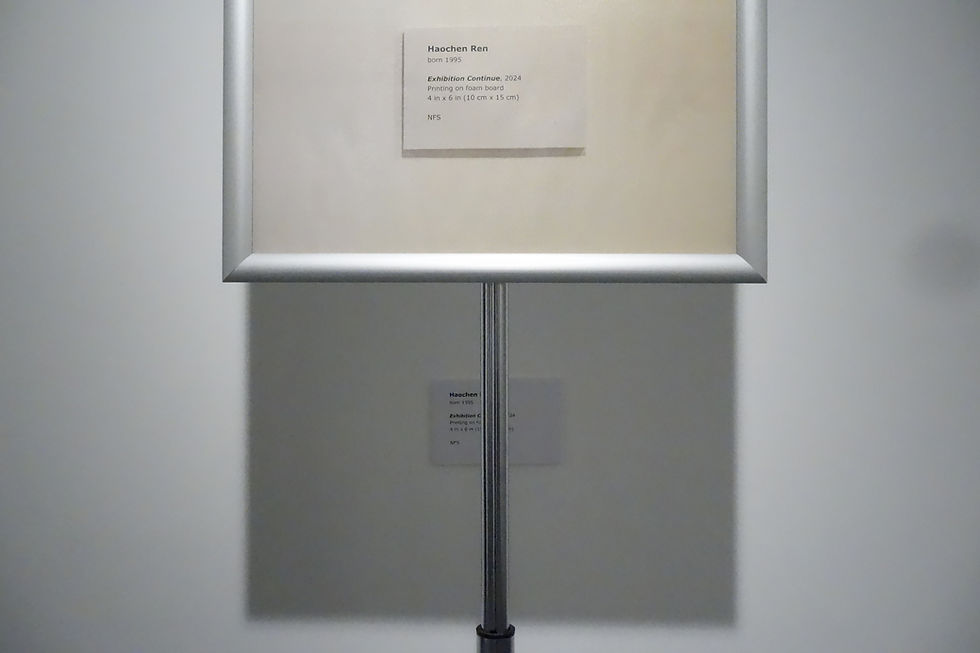

Ren revisits this strategy in Exhibition Continues (2024), a label that appears to extend the logic of its predecessor but with a new conceptual twist. This label, reading simply “Exhibition Continues, 2024,” functions less like a command and more like a time-based proposition. There is no direction, no “look left” or “look right,” no external thing to refer to, only a flat, looping statement that insists on the continuation of something that may not have begun, may no longer exist, or may be entirely internal. The viewer is implicated not in a visual game but in a temporal one. The exhibition “continues”, but where? How? With whom? In this sense, the label doesn’t just reflect on the structure of art viewing; it quietly reframes the viewer's presence as the work itself. The exhibition continues because you are here.

Ren's work draws our attention to the numerous terms used to describe the people who interact with art: viewer, reader, visitor, observer, participant, performer, spectator, co-producer, collaborator, and member of the public. Each term defines a role, a type of distance, and a degree of agency. Yet none of them quite describe the kind of subject Ren's work requires. His audience is both central and peripheral: activated but constrained, visible but voiceless. We do not simply "look" at the label, we perform it. The work exists not because of what it says but because someone is standing there, parsing the logic of its statement, wondering where the rest of the artwork is.

But that space, the one between the viewer and the artwork, between intention and interpretation, between statement and meaning, is precisely where Ren's art lives. There is always a gap between the participant and the artist, the reader and the meaning, the spectator and the institution. The public may execute the artwork through their attention or presence, but they are not given the power to originate it. Ren's work highlights this tension and refuses to resolve it. His labels are minimal, but they are also heavy with authorship. They invite participation while reminding us that participation is not the same as authorship. The public is never quite the creator; they are the trigger, the echo, the reflection.

This investigation into the power of naming reaches another level of subtlety in The Museum (2022). Installed inside an abandoned café at London’s Billingsgate Market, the work didn’t just borrow space; it borrowed objects and transformed them. Small labels affixed to the café's existing items: a counter fridge, a microwave, and an oven. Each label listed the object's name, its function, and its role in the café. These were not altered, polished, or curated for aesthetic appeal; they were simply renamed. Their everyday use became their medium. A display fridge was now 'An over counter fridge(curved glass) used in London England in the 2020s.'

An Over Counter fridge helps sellers maximise sales of their chilled food and drinks. Having products such as cheese, cooked meats, and fruit attractively displayed directly encourages impulse purchases and sales. Invented in the mid-20th century.

These short statements were quiet declarations of value, not of cultural significance, but of presence, of utility, of having existed and served.

Unlike the classic conceptual gestures of Duchamp or Broodthaers, who often stripped objects of their function to reposition them as pure art, Ren retains the object’s original life. He doesn’t decontextualise the fridge; he contextualises it differently. The artwork exists in the doubling: a fridge and a sculpture, a label and a joke, a museum and a café. That doubling also transfers authorship. The objects remain what they are, but through a simple act of designation, a label, they’re temporarily absorbed into the institution of art. The artist’s role is minimal but undeniable. This is not simply a gesture of elevation; it’s a proposition.

In the exhibition system, the public is seen as the executor, the responder, and the user of the artwork, but rarely the one who initiates the claim. And Ren's practice makes this visible. We have many words to describe those who engage with art: viewer, participant, reader, observer, performer, co-producer, and collaborator. Each carries a suggestion of activity, even intimacy. But none of these terms substitutes the one word we rarely assign to the public: artist. Even in the most open-ended, participatory practices, there remains a gap, a structural boundary between the one who names and the one who responds.

Ren never denies this. In fact, his work depends on it. In no title, Exhibition Continues, and The Museum, the gesture is his. The label carries his name, the year, the claim. But instead of using that authorship to fix meaning, he uses it to fracture it. The viewer isn't asked to interpret a finished work; they're asked to stand in the space between instruction and meaning, between object and label, between institution and gesture. The artwork only "continues" because someone is there because someone hesitated at a line of text on a white card and wondered: Is this real?

These are not works that offer answers or conclusions. They are works that persist. Gently, with remarkable precision, Haochen Ren invites us to look again—not at objects, but at the frames that tell us how to look. And in doing so, he shifts the question of art from what is on view to what is at stake. What if the label lies? What if the artwork is already over? What if the museum exists only in the moment we agree to believe in it together?